By: Hallmon Hughes

What is a battleground? A battleground is a “a piece of land on which a war or battle is fought.” While academics used to be about building up students and providing them with skills for the workforce, over time it has become a breeding ground for propaganda and political oppression.

On March 2, 2020, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill released a “Free Speech Report,” which surveyed their undergraduate students on campus climate (Larson and Ryan, 2020). Instead of asking questions about specific political events on campus, the researchers focused on campus climate with regards to daily activity. UNC Chapel Hill is an interesting campus because it is a very selective public institution and furthermore is located in a swing state. The researchers were surprised to find that 25.5% of the respondents said it would be appropriate to “create an obstruction, such that a campus speaker endorsing this idea could not address an audience.” Of the 25.5%, 19% were self-identifying liberals, while conservatives and moderates were only 3% each. In addition, more than 3% of liberals viewed “yell[ing] profanity at a student” for endorsing an objectionable idea was appropriate.

The study also found that 68% of conservative students self-censored, compared to only 24% of liberal students, noting that “anxieties about expressing political views and self-censorship are more prevalent among students who identify as conservative.”

In addition, almost a quarter of conservative students noted that they were more than slightly concerned that fellow students would “file a complaint against them” for discussions related to classes that they had with each other. Out of the liberal students in the study, 57% noted that they have heard “disrespectful, inappropriate, or offensive comments” about conservatives. Of moderate students, 68% noted hearing “disrespectful, inappropriate, or offensive comments” about conservatives at least several times a semester.

With regards to campus interaction, only 3% of conservative students noted that they would not be friends with a liberal, while almost 25% of liberal students noted that they would not be friends with a conservative. The authors concluded that, “Self-identified conservative students do in fact face distinct challenges related to viewpoint expression at UNC.”

While this study was on just one college campus, other studies have shown similar trends with regards to academia. Another study, which sampled 494 books with an ideological thesis, found that a mere 2% of Harvard University Press publications represented perspectives of conservatives or classical liberals (Gordon and Nilsson, 2011). Conservative viewpoints are not given fair consideration in the academic field. This is also true with regards to K-12 and professor positions in academia.

A 2017 poll by Education Week, a trade publication, noted that 41% of K-12 teachers identified as Democrats, while only 27% identified as Republicans. These statistics indicate a 12 point higher percentage of Democrats as teachers in K-12 schools than the general public. Therefore, Democrats are disproportionately recognized in the K-12 system. Furthermore, the disparity between political roles in universities is even higher.

A 2016 study that reviewed voter registration data for the faculty members of economics, history, communications, law, and psychology departments at 40 leading US institutions found that of a sample of 7, 243 professors (half of whom were registered to vote), 3,623 were Democrats compared to merely 314 Republicans (Langbert et al., 2016). This results in a 11.5 : 1 average ratio of Democrat to Republican professors. The researchers found the greatest disparity was in history departments with a 33.5 : 1 Democrat to Republican professor ratio. The authors estimated that active humanities and social sciences departments will vote at a ratio of 10 : 1, Democrats to Republicans, which is a 2 point increase from the disparity noted in 2004. Even left minor-party members exceeded Republican numbers in 72 of the 170 departments studied, noting that “Republican registrants were as scarce as or scarcer than left minor-party registrants,” in 42% of departments.

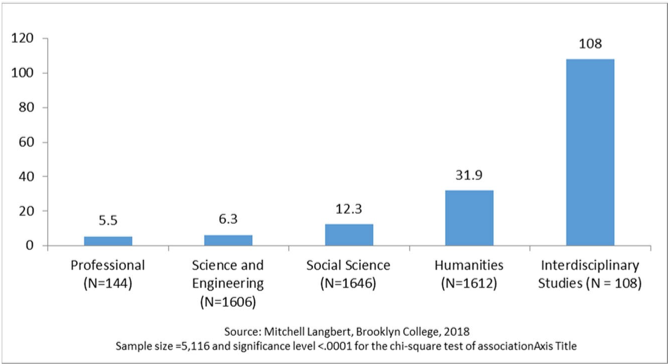

A more recent study, found that, “faculty political affiliations at 39 percent of the colleges in my sample are Republican free—having zero Republicans” (Langbert, 2018). In addition, 78.2% of the academic departments in the study were found to have either zero or a negligible amount of Republicans. From the 8,688 tenure track PhD.-holding professors in the study, who came from 51 of the 60 top ranked liberal arts colleges in the US News 2017 Report, the mean Democrat to Republican ratio was 10.4 : 1 (Langbert, 2018). The removal of data points from West Point and the Naval Academy increased the disparity to 12.7 Democrat professors for every 1 Republican professor. The disparity is increased in social science and communications fields, as is evidenced by the results of the study (which are listed below for your convenience).

Figure 1. Number of Democratic Faculty Members for Every Republican in Five Broad Fields

While I have nothing against left-leaning or leftist professors (as long as they do not actively work to persecute students with views other than their own), the disproportional exuberance of Democrat professors has had negative effects on the success of conservative students (Woessner et al., 2019). One study found that, even when controlling for demographics, family income, and standardized test scores, conservative students have a statistically significant greater decline in their grades from high school to college, as compared to their liberal counterparts. In addition, the study noted that the gaps between students were most pronounced in departments where the faculty are furthest to the left. The study also found that conservative students generally enter college with higher SAT scores and GPAs than their liberal counterparts, but have lower GPAs than liberal students by their fourth year of college, noting “ideological self-placement is the only variable in the model changing direction from high school to college.” Furthermore, students who noted that they opposed free speech had higher college GPAs than what was predicted based on their high school performance (Woessner et al., 2019). While some people may argue that high school GPAs are not indicative of college success, a study released by the National Association for College Admissions Counseling found that high school GPAs are the best predictor of college achievement (Hiss and Franks, 2014).

I am not sharing this information with you to criticize professors with Democrat beliefs, but rather to acknowledge that there are statistically significant differences between the college experiences of liberal and conservative students. I have been fortunate to have some left/left-leaning professors who are respectful of views other than their own and who encourage respectful dialogue in their classes. I have also had professors who have reacted in a negative light to my political views and used my political affiliation to make judgements about my character. There are two sides to every coin.

For every one story that is shared, there are several more who have no voice. I attend a lot of political conferences, each of which has students with harassment stories. These voices need to be heard. By addressing the double standards in education systems that tout “diversity and inclusion” I hope that one day we can live in a world where these terms are not abused to endorse some views and silence others.

References

Gordon, D. and P. Nilsson. “The Ideological Profile of Harvard University Press: Categorizing

494 Books Published 2000-2010.” Econ Journal Watch, 2011. Vol. 8(1): 76-95.

Hiss, W. C. and V. W. Franks. “Defining Promise: Optional Standardized Testing Policies In

American College and University Admissions.” The National Association for College Admission for College Admission Counseling, 2014.

Langbert, M. “Homogenous: The Political Affiliations of Elite Liberal Arts College Faculty.”

National Association of Scholars, 2018. Vol. 31(2): 1-12.

Langbert, M., A. J. Quain, and D. B. Klein. “Faculty Voter Registration in

Economics, History, Journalism, Law, and Psychology.” Econ Journal Watch, 2016. Vol. 13(3): 422-451.

Larson, J., M. McNeilly, and T. Ryan. “Free Expression and Constructive Dialogue at the

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.” 2020.

Woessner, M., R. Maranto, and A. Thompson. “Is Collegiate Political Correctness Fake News?

Relationships between Grades and Ideology.” EDRE Working Paper No. 2019-15, 2019.